If you’ve been following the online commentary about the ongoing protests in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), you know there’s been plenty of speculation about how digital communication technologies have aided, hindered, or failed to influence events on the ground. Opining without systematic evidence is all well and good—indeed, when done well it yields testable predictions about real-world outcomes—but at some point actual data must be brought to bear on these questions. One question I have found both interesting and testable is: to what extent are social media used by individuals in Arabic countries experiencing political unrest? An additional corollary question is, to what extent do social media serve as a conversation platform for a broader Arabic online public during times of widespread unrest?

To begin to address these questions, I focus in this post on Twitter, both because its ostensible revolutionary power has been widely discussed and because data from it is fairly easy to collect and manipulate. Country-specific hashtags such as #egypt conveniently collect relevant tweets, and until recently it was possible to create and save public hashtag archives using free tools like TwapperKeeper. Unfortunately, on March 20, 2011 Twitter changed its terms of service to disallow public sharing of tweet archives. So, shortly before the change went into effect, I exported archives of several MENA-related hashtags from TwapperKeeper for analysis. The subset of the data presented in this post totals over 5 million tweets, with each entry including the author’s username, the full text of the tweet, the date and time posted, and other metadata. They do not, however, include the user’s location field, which I had to collect separately based on lists of unique users posting to each hashtag. Combining the chronologically-ordered hashtag dataset with the location data allows me to plot in time series the number of tweets in each hashtag whose authors claimed to be in the country in question. A little additional filtering helps me capture the extent to which each hashtag was used by individuals located in other Arabic-speaking countries.

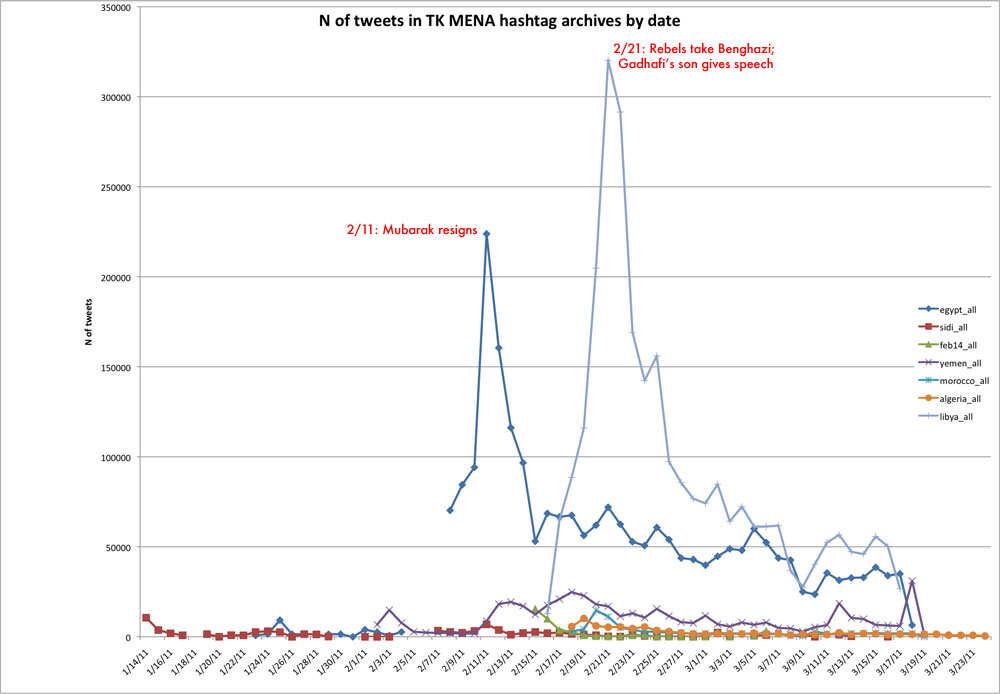

But we’ll get to that in a second. First, let’s have a look at total tweet counts over time for the TwapperKeeper archives of seven major MENA hashtags: #egypt, #libya, #sidibouzid (Tunisia), #feb14 (Bahrain), #morocco, #yemen, and #algeria. Each data line begins on the date of the archive’s earliest tweet. The total N of tweets represented in this chart is 5,888,641.

A couple of things jump out at me looking at this plot. First, Libya and Egypt clearly grabbed the lion’s share of the attention, attracting several hundreds of thousands more tweets on their respective peak days than the next most popular hashtag. Both peaks were pegged to significant events on the ground—Mubarak’s resignation in Egypt’s case, and the taking of Benghazi and a major speech by Saif al-Islam Gadhafi in Libya’s. The other hashtags register far less overall activity in comparison. One hypothesis is that tweet volume in different countries may be driven by the amount of newshole devoted (by CNN, NYT, al-Jazeera, etc.) to events in that country, but more data would be needed to verify that.

The next logical question here concerns where these authors are located. Are they primarily residents of the countries in which the events are unfolding, concerned observers from culturally and physically neighboring states, or international spectators (perhaps including diasporic populations) commenting from afar? Answering this question entailed creating an automated word filter that placed each user-provided location into one of four categories: 1) in the hashtag country; 2) in the greater Arabic region (defined as the following countries: Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestinian Territories, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen)1; 3) outside of both the hashtag country and the Arabic region; and 4) no given location. The filter counted both instances of the country name and cities in each country. (If anyone is interested in specific details on what the country filters included, let me know and I’ll write up another post on it.) The total N of tweets analyzed for all six countries profiled below is 3,142,621 (#libya is not ready yet for reasons I explain later), some of which overlap due to the presence of multiple hashtags.

Between 25% and 40% of unique names in each hashtag lacked any location information. These include users who left the field blank, deleted their own accounts, or had their accounts suspended. Being essentially unclassifiable data, tweets by such users are excluded from the following charts.

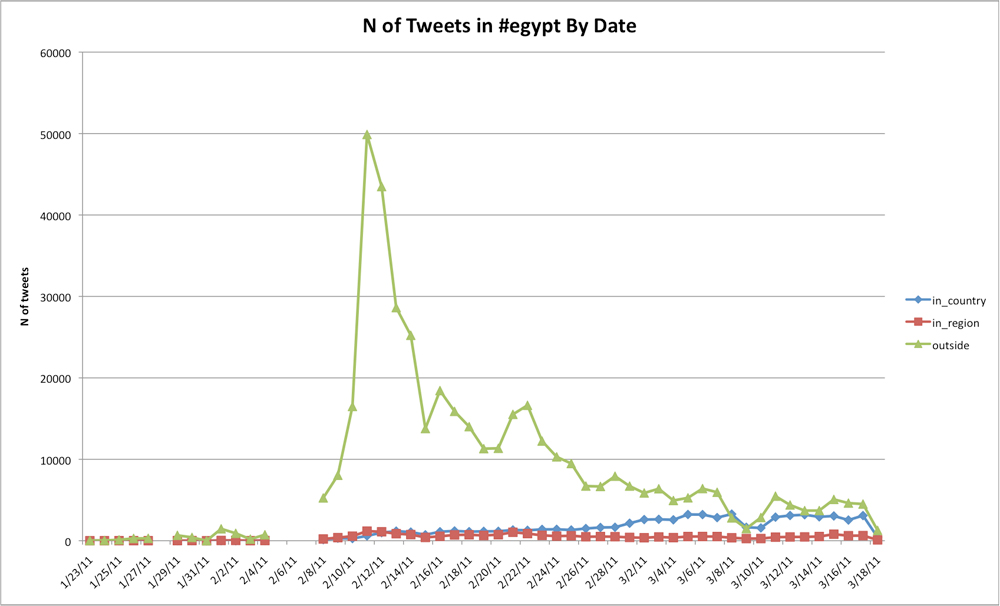

First we’ll have a look at #egypt:

Here we can see a pattern that will recur throughout most of the hashtags: the major spikes are driven by individuals from outside of both the country and the broader Arabic region (who are almost certainly responding to media reports). It is only when outside attention dies down that local and regional voices even begin to achieve parity with their international peers. (Note that the conspicious gaps between 1/27 and 1/29 and 2/4 and 2/8 are due to TwapperKeeper archival overload. Some of the other hashtag archives feature similar gaps. This missing data is frustrating, but what is present is valuable nevertheless.)

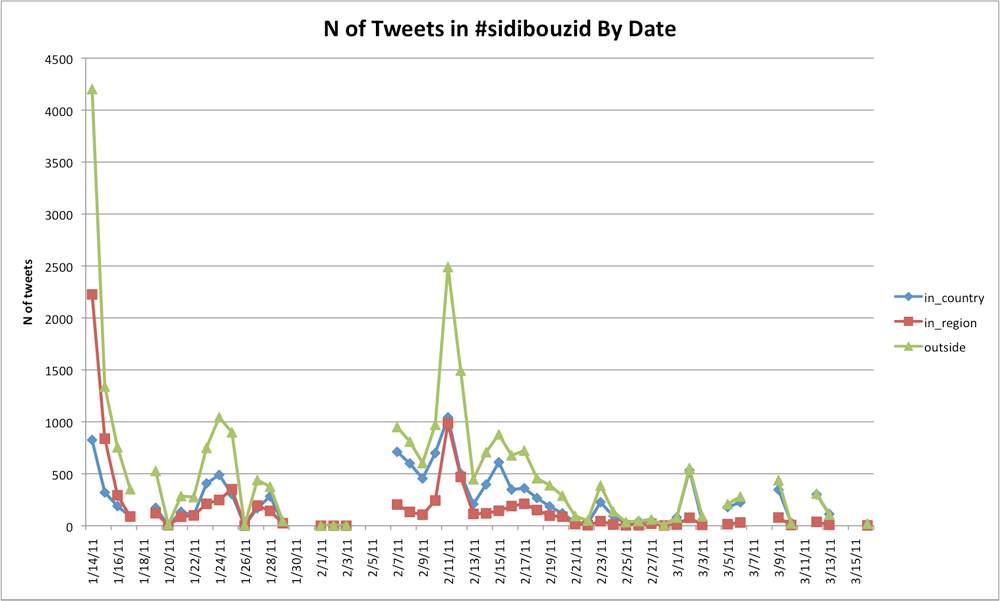

Next is #sidibouzid (Tunisia):

A pattern similar to Egypt prevails here, wherein outsiders usually dominate when the total N of tweets tops about 1,000.

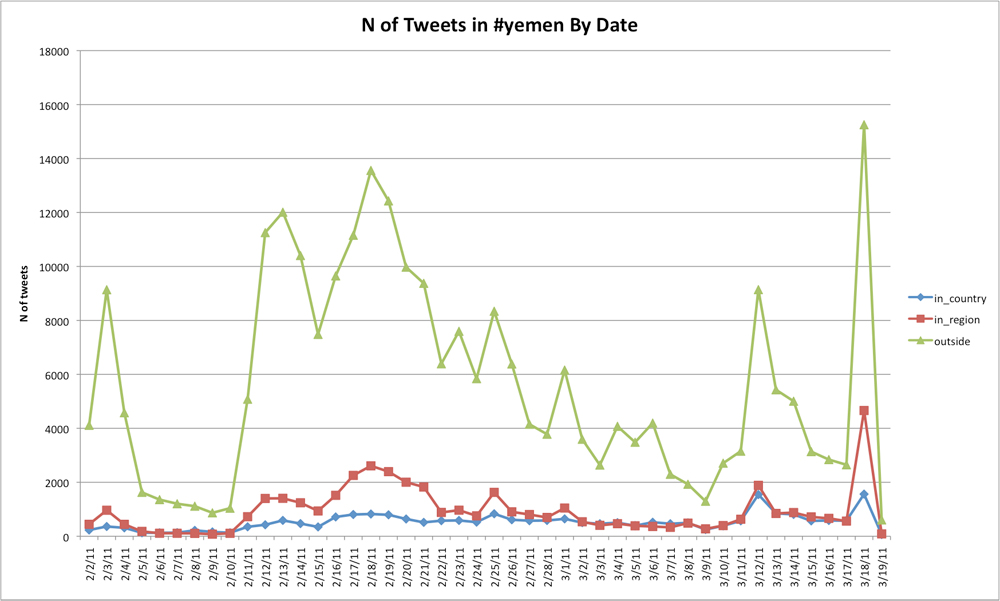

#yemen:

This archive again displays the by-now familiar pattern, with the major difference being that regional tweets often exceed local tweets. This is most likely due to Yemen’s low internet penetration (1.8%).

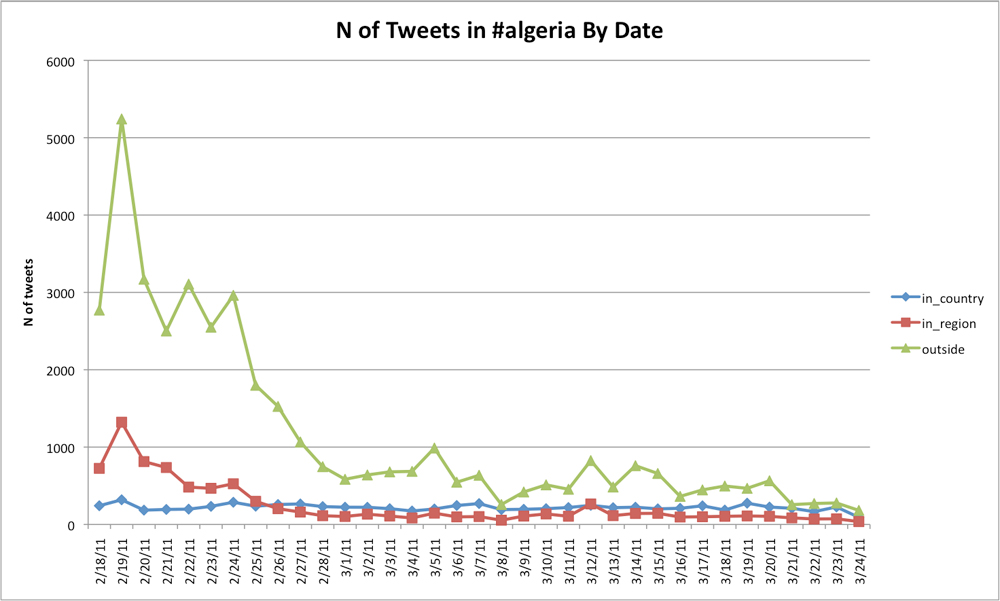

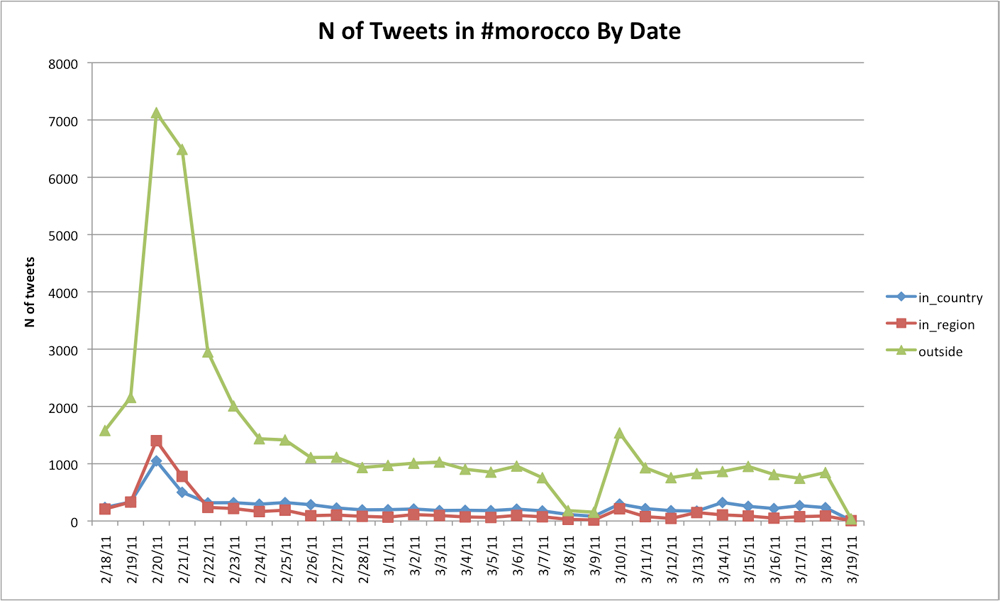

#algeria and #morocco are very similar, so I’ll present them next:

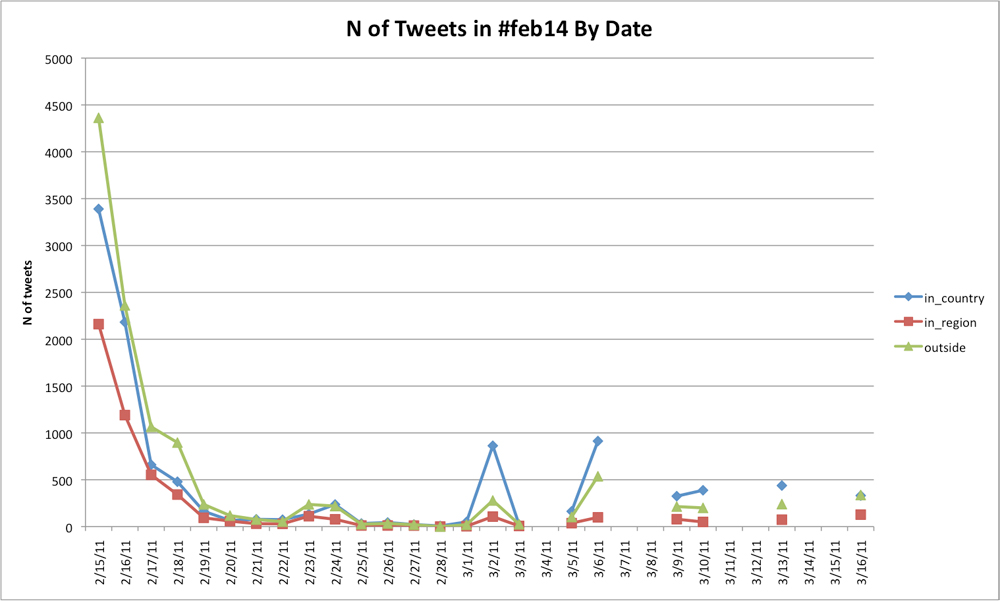

The final hashtag archive in this post is for #feb14 (Bahrain), which unfortunately is rather incomplete. But once again, outsiders outnumber locals and regionals at higher total Ns, while locals take over at lower Ns.

I am still working on creating a comparable chart for the #libya archive, but it is difficult to apply the country filters to such a large N of unique users. A preliminary analysis of its first five days (5/16-5/20) that I presented at the Theorizing the Web conference last month showed that as the total N of tweets increased, the proportion of tweets from Libya decreased. With a net penetration rate of only 5.5%, it would not be surprising to discover that the entire hashtag followed the established pattern.

What does it all mean?

The evidence from the hashtags analyzed here indicates that, at least in the early days of the Arab Spring, Twitter served primarily as a platform for communication by international observers about the events. There is also limited evidence of a pan-Arabic public conversation within these hashtags, but this is not their primary purpose. Both phenomena are definitely episodic and appear strongly event-driven. As in the Iranian protests of 2009, Twitter seems to fall into Aday et al.’s (2010) “external attention” category of new media roles.

Of course, this doesn’t necessarily mean that Twitter use is politically inconsequential. Attentive global citizens and diasporic populations could, for example, use it to promote action opportunities to sympathetic followers. They may also retweet content from local users liberally, thus amplifying the latter’s voices beyond what the above charts imply. For that matter, local users themselves may find these hashtags useful for sharing and verifying local news at times when they are not swamped by outsiders. Answering questions like these will require textual analysis, and it is unlikely that automated methods will suffice (except for the RT question). I’m envisioning lots of content analysis, translation from Arabic and French, and input from subject matter experts in my future…

A few caveats about this data are in order. First, they do not include all tweets posted to the hashtags for the given time periods. TwapperKeeper functions by drawing samples from the Twitter search API, so there is no way to know exactly how many tweets were posted without access to the definitive Twitter-hosted databases. Second, like any continuously-running software program, TwapperKeeper can fail, as can be seen in the chart gaps above. The reason I chose to analyze #feb14 and not #bahrain is that the TK archive for the latter contains a two-week gap that included the “official” start date of the protest, February 14. Third, it is possible that other hashtags not analyzed here served different functions. Some MENA hashtags have Arabic titles, and it seems unlikely that these would fall under the external attention banner. I have archives of some of these for Egypt and am interested in collaborating with an Arabic-speaking expert to interpret them. Fourth, other social media services such as Facebook may serve different protest-related functions, depending on the country’s level of net penetration and service diffusion.

Then there is the question of whether the authors’ stated locations are accurate. Critics of my method will probably hasten to point out that many Twitter users changed their locations to “Iran” during the 2009 protests in that country. If this phenomenon occurred to any significant extent during the Arab Spring protests, it would significantly reduce the value of the current research enterprise. However, there are several reasons I doubt this to be the case. For one, to my knowledge there was no high-profile campaign to convince Twitter users to change their locations to any given Arab Spring country. With simultaneous protests ongoing in multiple countries, such a campaign (if it existed) would either have had to target one country or spread itself among more, either way diluting its overall impact. Also, my country filters included many city names, which outsiders would be unlikely to know offhand. Finally, if large numbers of international users had changed their locations to the protest countries, the filters probably would have identified far more users as local than they did. The fact that comparatively few users self-identified as local strongly suggests that the Iran strategy was not widespread in this case.

I am interested in your questions and suggestions about my methods and interpretations, so please let me know what you think in comments. If there are other analyses you’d like to see, I might be able to pull them together.

Note:

[1] Credit for this list of countries goes to Phil Howard, who recently published a book on digital communication technologies and politics in the Islamic world.

Thanks for some very interesting data and analysis. Two comments:

One, why did you choose to examine #Egypt instead of #Jan25? During the revolution, I got the sense that people in the know, especially Egyptians themselves, would primarily use #Jan25 instead of #Egypt. As the revolution entered its consolidation phase after Mubarak’s resignation, the use of #Jan25 anecdotally seemed to decline and #Egypt seemed to increase. Assuming that’s correct, it may explain why there’s such a large gap between outside and in-country tweets and why in-country tweets increased over time.

Two, the #Feb14 data seem to support what I suggest above. People in the know used the revolution’s start date instead of the country name. As the data show, even for large-n dates, the gap is significantly smaller compared to #Egypt. And for small-n dates, in-country outnumber outside tweets, something we don’t see for #Egypt. But all of that could just be that outside Twitter users just care less about Bahrain than Egypt.

Thanks again and I look forward to seeing how this all develops!

Jason,

Thanks for your comments. My main criterion for choosing the hashtags was archive size—most of the country name hashtags contained far more tweets, and thus more dramatic peaks and valleys, than the “revolutionary” date-based tags. In cases where the latter were larger than the former, I chose the latter. But this post represents a work in progress, and I do plan on investigating the differences between country and revolutionary hashtags. Like you, I fully expect to find some.

Another issue here is that the country tags may contain a significant amount of noise simply because they host a wide range of content, much of it likely unrelated to the protests. For example, TwapperKeeper’s archive for #bahrain had been accruing tweets for over a year before 2/14/11, and one of the main topics for 2010 seemed to be Formula 1 racing (this is based on my very cursory eyeballing of the data). To get at these potential differences in a systematic way, content analysis or a similar textual method would have to be used.

I just noticed that as well; frankly, I don’t think your outcomes (at least in terms of the question of in-country vs. outside) can be considered accurate without analysis of #jan25 in the case of Egypt. While #egypt may have been a more popular hashtag, anecdotally, I can say that Egyptians weren’t using it. They chose #jan25 as their own; I watched friends in Cairo debate it. I support your thesis that they are the minority when it comes to overall tweets, but it was nevertheless theirs.

Could it also be possible that the actual number of locals is dimished due to security fears? I.e residents of the countries in question would rather not reveal their locations for fear of retribution?